How can we prepare workers for the age of generative AI? Consider the Human Skills Matrix.

March 26, 2024

A little more than a year after Open AI released Chat GPT, a consensus appears to have taken shape: generative AI is revolutionizing the way we work.

Astonishingly, McKinsey predicts that 30 percent of all current work hours will be automated by 2030, and LinkedIn researchers find that, also by 2030, core skills will change for 65 percent of workers.

But how exactly will workforce skills need to change? And what can workforce-learning experts do to prepare workers for transformations to come?

The answer may lie in human skills. And the Human Skills Matrix, developed by researchers at MIT’s Jameel World Education Lab (J-WEL), can offer guidance.

Why the value of human skills is rising.

Generative AI appears to be lifting an already rising demand for soft or human skills, which are believed to protect workers from technological disruptions in labor markets. Human skills, the thinking goes, transfer from job to job because they cross multiple industries and roles. Moreover, human skills include mindsets needed for lifelong and agile learning—both useful in a world in flux.

But generative AI adds a new twist. As AI performs more technical tasks, workers may soon spend more time on relationships—interacting with coworkers, clients, and suppliers. In this environment, human skills could prove especially valuable.

“A moment like this compels us to think differently about how we are training our workers,” write Aneesh Raman and Maria Flynn—executives at LinkedIn and Jobs For the Future respectively—in a recent essay in The New York Times.

According to Raman and Flynn, workforce learning has tended to focus on technical skills, under the belief that they secure “future-proof” and high-paying jobs with rapidly growing technology companies. That prioritization of technical skills, Raman and Flynn argue, “needs to change.”

“Today the knowledge economy is giving way to a relationship economy,” conclude Raman and Flynn.

Experts have tended to hold divergent views on human skills. The Human Skills Matrix integrates them.

Despite their recognized value, human skills have proven notoriously difficult to define, with dozens of theories competing for prominence. Even deciding on what to call these skills has been contentious.

“There is so much variation in what people call these skills: social skills, soft skills, transverse skills, etc. And there’s even more variation in the skills that these frameworks highlight,” wrote GOF Founder George Westerman when researchers at J-WEL released the Human Skills Matrix.

This ambiguity and disagreement led Westerman and colleagues at J-WEL to embark on an effort to synthesize divergent views into a comprehensive framework.

“That’s why we undertook this effort—to identify and structure a set of human skills that we can believe in, and that others might find useful,” Westerman wrote.

To develop the Human Skills Matrix, or HSX, Westerman and colleagues at J-WEL analyzed 41 human-skills frameworks and thought leaders in the field. This process yielded an initial set of 44 skills, and from that set, the most important skills were identified by a panel of experts. Related skills were then grouped together in the HSX.

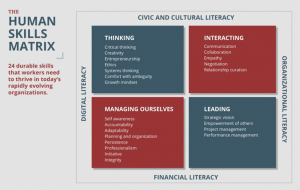

The Human Skills Matrix (HSX). The top row represents applied skills; bottom row, managed skills; left column, intrapersonal skills; right column, interpersonal skills. Literacies along borders are foundational for human skills.

The Human Skills Matrix can help learners, employers, and workforce-learning providers identify and advance toward valued human skills.

Individuals can use the matrix to self-assess and determine what skills they may need to learn; training providers can use it to plan curriculum and set learning objectives.

The HSX groups in-demand skills into four quadrants in 2×2 matrix. In commentary on the matrix, Westerman and Glenda Stump, then a research scientist at MIT, explain that skills in the top row are “applied,” while those in bottom are “managed.” Likewise, skills in the left column are “intrapersonal (within ourselves)” and those on the right “interpersonal (with others).”

The matrix also contains, along its borders, literacies that are foundational to human skills. Westerman and Stump explain that workers need to be able to use these literacies to act effectively:

- Financial literacy: make informed decisions about financial resources.

- Civic literacy: participate in or initiate change within the community.

- Cultural literacy: interact effectively with individuals from diverse backgrounds.

- Digital literacy: function effectively via digital platforms.

- Organizational literacy: know how things get accomplished within an organization.

* * *

Now more than four years old, the matrix is as relevant as ever. As generative AI scrambles what skills organizations need to remain competitive and effective, the HSX offers a steady vision for learning amid a technological revolution.

Back to All News & Research